|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It started with receipts for the bodies. My sister and I were sorting through the detritus of our parents’ lives — commendations to my father from Rotary, my fifth-grade essay on beetles, our mother’s set of twenty finger bowls, ash trays, pink lipsticks from the sixties, photos of sailboats and cocktail parties, golfers in plaid shorts, and one of my father with Gov. “That’s the family plot,” my sister told me when I showed her the letter. “In Cincinnati.” I had been to weddings in Cincinnati, but never funerals, so I hadn’t seen the towering marker that came to reside on the knoll in Spring Grove Cemetery that was designed by Frederick Law Olmstead who also designed Central Park as well as Golden Gate Park in San Francisco where I now live. “Let’s save it,” I said. “What else?” I studied a wad of papers. “Receipts,” I said. “Oh, wait.” I read them again. “Holy cow,” I said. “They’re receipts for exhumations.”

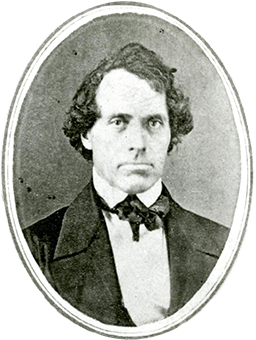

Each family has its creation myth. Ours was the Scots-Irish Gambles coming down the Ohio River on a flat boat and settling in Cincinnati. They had intended to go to Illinois. The father George, a farmer, hoped to preach as a Methodist minister, but his son James fell ill with cholera. Resting in Cincinnati while James recuperated, they decided to stay. We know the rest: how James became a soap-maker using the byproducts of pigs from the slaughterhouses; how during the Crash of 1837, he teamed up with his brother-in-law, William Proctor, who made candles, to buy in bulk and survive tough market conditions. Religious men, they built their company on honesty and integrity as well as steely ambition. But what most interested me was that they lived on the Ohio River, right across from the slave state of Kentucky.

We still feel the tremors from 19th Century America. Like today, it was a time of rapid industrial and technological changes that displaced ways of life and forced culturally diverse people together, created vast and concentrated wealth, saw an emergence of the Second Great Awakening in which religious

I was well aware of our creation myth, but there were unanswered questions. What, for instance, did those ancestors whose names were on those receipts think of slavery? I began to resurrect their views like bodies from a churchyard, starting with visits to Cincinnati, Ohio and Maysville, Kentucky, lurking in historical societies and museums, especially the Cincinnati Museum Center in the Union Train Station from which my father departed for WWII. I talked to historians and librarians. I As for me, I had the privilege to trace my roots back to the 1600s — our family’s migration to Ireland from Scotland under King James, their two-hundred years of farming, their plight at the end of the Napoleonic Wars that sent them to America, this new country that was eager to accept them and offer a path to prosperity. My white family came voluntarily, their history documented in ship logs and letters and diaries and photographs and commendations from the Rotary Club. Not so most African-Americans whose families descended from slaves.

It was in that book that I read how a mixed-race young woman was raised as a daughter in a white household, only to be sold off when her mother died. The girl could pass as white. So outraged were the people of Lexington to witness this beauty being sold at auction that the appetite for slavery began to wane. Fortunately for her, she had caught the eye of Calvin Fairbanks, a Presbyterian minister whose mission was ushering slaves to freedom. Purchased by the minister, the young woman was later married into a Cincinnati family of consequence. Who was that family? Even our family, with its predominantly Scots-Irish coloring, has its share of aunts and cousins of extraordinary beauty and dusky skin.

In the summer of 2010, I traveled to Ireland and the town of Omagh where I saw a recreation of how Protestant-Irish farmers lived. There, in an emigration museum, I saw the kind of ship my family would have sailed on and found in the ship’s log of the Lucretia the recorded names of my ancestors: the Georges and the Jameses, the Marys, the Elizabeths, and the Olivias — two generations of Gambles that had made it across the sea.

I hadn’t intended to write about the underground railroad or about race or religion, about children separated from their parents, or the challenges of being a woman in the 19th Century. I just wanted to understand. But at some point, the research In digging them up, I discovered my own ancestors to eulogize. My great-great-aunt who perished nursing the freed black soldiers who had volunteered for the Union Army. My great-great-great-grandfather, the state supreme-court judge who refused to honor the Dred Scott Decision. My great-grandmother Mary whose appetite for travel, visionary architecture and social progress informs my life today.

Digging Up Ancestors Copyright © 2018 by Terry Gamble. All rights reserved. |

James Gamble

|

|