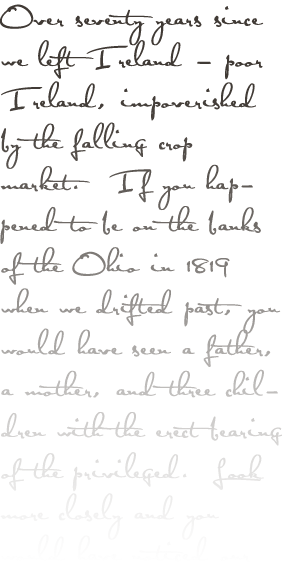

Over seventy years since we left Ireland — poor Ireland, impoverished by the falling crop market. If you happened to be on the banks of the Ohio in 1819 when we drifted past, you would have seen a father, a mother, and three children with the erect bearing of the privileged. Look more closely and you would have noticed our frayed clothes, my brothers’ pants too short, my dress hanging limply on my ungenerous chest. At fifteen, I must have looked a sight, having wailed across that ocean — a six-week passage of wailing and puking, and wouldn’t you have wailed if you were pulled away from that bonny youth who had kissed your unkissed mouth with such urgency as to make you want to lie right down and unbutton something?

We were Ulster Plantation Irish, which is to say that we were Scots. We had come to America to pray and to prosper. Come to America because America wanted us — this too-new country with land and trees to spare, but not enough people. I can see him now — my father standing at the bow of the flatboat he had christened “The Ark of the New World” but which to us felt more like the belly of the whale. Josiah Givens — a man of strong conviction and tepid Calvinism, whistling a passage from the Eroica Symphony and wishing he had more to show for himself.

“Ye shan’t be finding many symphonies here,” said my mother, resting a hand on her queasy stomach. “Ye’d be hard pressed to find a fiddler.”

It wasn’t just seasickness that affected her, but the twinges of an early pregnancy going awry. Having lost four already, she knew she would lose this child, leaving only three — James, myself, and Erasmus.

It was early autumn. Our father had hired a pilot to navigate the rocks and fend off pirates who would rob and possibly murder us. By now we had grown accustomed to the animal carcasses and half-eaten limbs that washed down from the hinterlands. We scarcely noticed the stench until James shouted, “Look, Da! ‘Tis a body in the snag!”

Dazzled by the sun on the water, we followed the direction of his finger, hoping it might be a felled tree since there were so many being cleared. The figure’s head dipped below the surface, its bloated chest lifted, its arms flung wide as if to embrace the sky.

“Lord help us,” said the pilot. “Niggers clogging the river.”

I gaped at the body.

“You’re not even going to pull him out?” I said to the pilot, tapping my parasol upon the deck. In Ireland, we would have helped anyone — even a Catholic — but you’d think this was a sheep for how little vexed he was.

“And then what, missy?” said the pilot. “We haven’t time to bury it. And why bother? If someone comes by and thinks they can fetch a price… well, then.” The pilot spat. “In the meantime, my contract is to deliver you.”

“I feel sick, Da,” said Erasmus.

We had all been sick. Nothing stayed down after that first week out of Belfast, and now our mother, wan and edgy, spent most days on her cot. So many long days staring at the horizon, and my saying, There! Land! But it was only a fog bank teasing us until — finally! — Nova Scotia.

We arrived in Philadelphia diminished. Halfway across the Atlantic, paralyzed by doldrums, the crew of the schooner Lucretia had pitched our piano overboard. And then to have my mother’s trunk of good dresses and most of our books stolen off the landing in Philadelphia. We had watched as seven shirtless black men had loaded onto a stagecoach what was left of our belongings. It scarcely mattered that we still had our Minton china and our silver candlesticks.

Hottentots. That’s what they were to us. My skin had burned — mostly from the sun, and there was Jamie jabbing me in the ribs, pointing at a half naked Negro and saying, Livvie, did you see that?

Honestly, Jamie, this is America.

America — where it was said that the Indians were cannibals.

Every day on the river, we would see distant fires clearing forests for settlements. We’d heard tales of a comet and how an earthquake had reversed the current, reddening the river with iron rich soil. Now at sunset, the smoke rendered the sky hellish and glorious as Dante described, THE DIVINE COMEDY being my only salvaged book other than the Bible. With the strange weather and the crops failing, the Book of Genesis had collided with the Book of Revelation, and portents could be gleaned in anything.

“You saw that body, Josiah,” said my mother. “What next?”

A flock of geese blackened the sky. To the south lay Kentucky: slave state. To the north was Ohio: free. We drifted past limestone escarpments restraining forests of beech trees ten hands wide. “This is ours,” said our father. “Our new Eden.”

Excerpt from The Eulogist by

Terry Gamble. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced without written permission from

HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022

|